by Kenneth Florey

My journey with suffrage artifacts began in 1989 when a trade journal for book dealers, AB Bookman’s Weekly, asked me to write on article on the subject for a special issue on women’s studies they were preparing in conjunction with the 11th Annual National Women’s Studies Association Conference held on June 14-18 of that year at Towson State University in Maryland.

As background, I had access to the collection of Frank Corbeil, then one of the outstanding accumulations of suffragist material in the country. I have always been interested in causes and their associated ephemera. There is something vital in movements that inspires so many of their adherents to essentially devote their lives to effect changes in our social fabric.

But as I viewed the suffrage objects in Frank’s collection, there was something about them that especially attracted me. The buttons were not designs produced by various badge makers that were sold to anyone, but they were creations of activists themselves. The postcards reflected period reactions to the movement, both pro and anti, and gave me a strong sense, not of collectibles, but of a meaningful cultural history.

NOT SIMPLY COLLECTABLES,

BUT EVIDENCE OF A RICH CULTURAL HISTORY

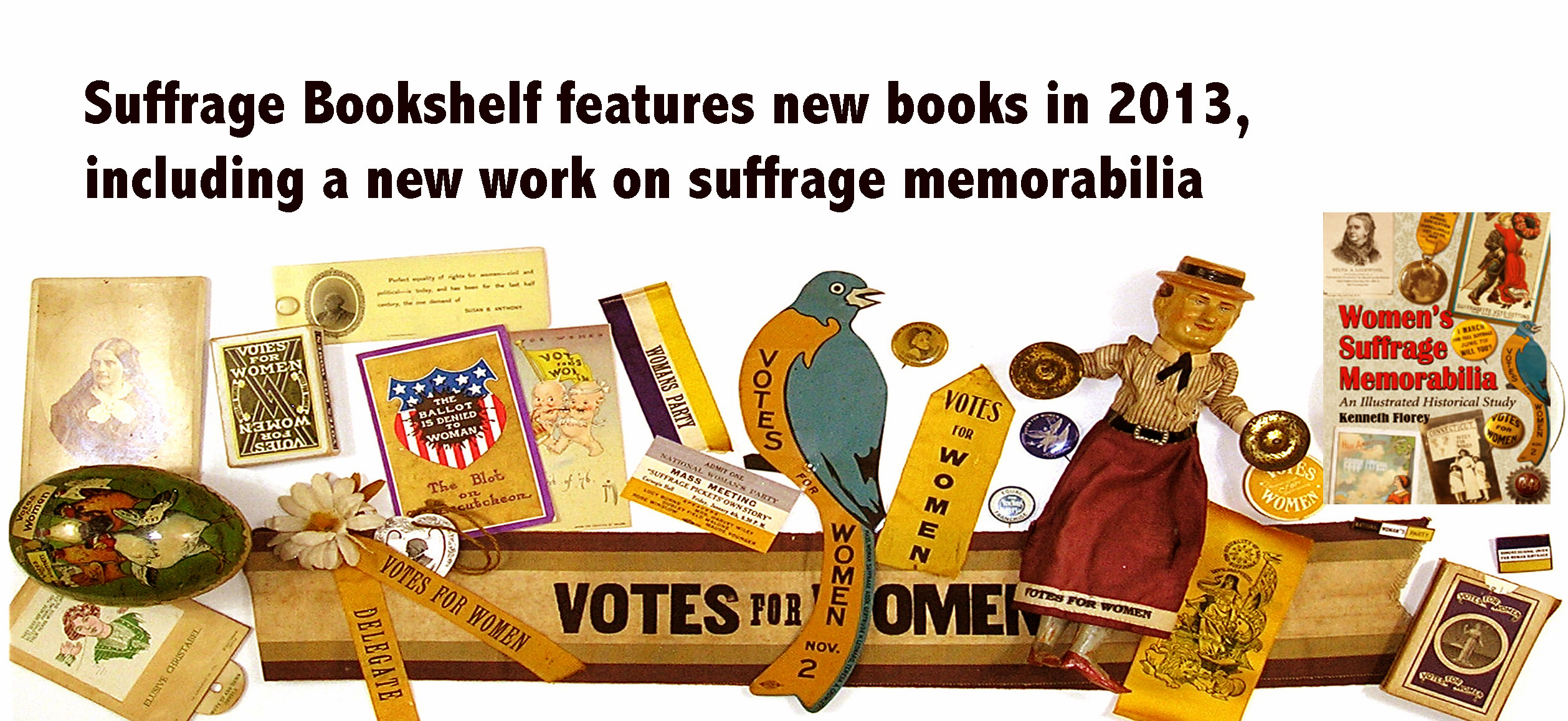

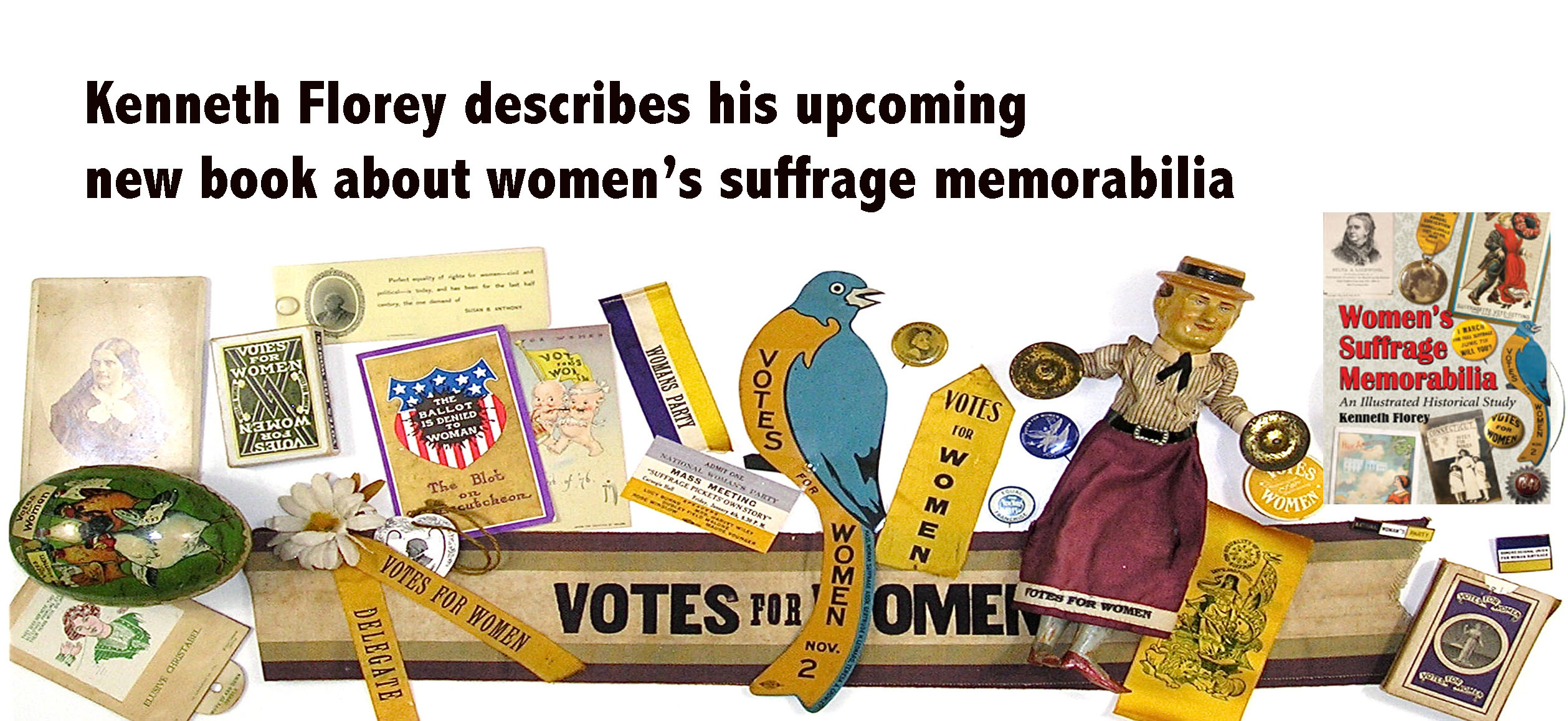

This is how my collection of suffrage material began. It’s a collection that grew from tiny to respectable and finally to one that I believe is the largest such accumulations in private hands in America. At present it consists of about 250 different buttons and badges, approximately 1900 postcards that deal specifically with suffrage, 75 pieces of suffrage sheet music, and many three-dimensional pieces such as a hunger strike medal. The medal was presented to English prisoners who refused to eat while they were in prison and eventually force fed. The National Woman’s Party issued a “Silent Sentinel” pin to protestors who demonstrated outside the gates of the White House. Activists used suffrage board and card games to promote the cause, as well as suffrage china that was distributed at movement tea and dinner parties.

As my collection grew, I learned more about movement history and developed close friendships not only with other collectors but also with scholars both here and abroad. Included among these is a direct descendant of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. And, fortuitously, one of my editors at McFarland is probably related to Inez Millholland, a martyr for the suffrage cause, whose death was in part caused by exhaustion and exposure while she was out campaigning.

A collection that consists simply of objects is meaningless unless one understands the context in which that memorabilia was produced. It was the desire to know what suffragists themselves thought of their material, the stories behind their manufacture, and the involvement of memorabilia in the campaign for equal rights that encouraged me to do research for my book. The stories are fascinating.

A collection that consists simply of objects is meaningless unless one understands the context in which that memorabilia was produced. It was the desire to know what suffragists themselves thought of their material, the stories behind their manufacture, and the involvement of memorabilia in the campaign for equal rights that encouraged me to do research for my book. The stories are fascinating.

HIGHLIGHTS OF SUFFRAGE STORIES REPRESENTED BY COLLECTABLES

There was the suffrage prisoner who was accused of “biting” her warden when the official tried to rip off her blouse and he was stuck by a suffrage pin. There was the anti-suffragist who wrote to the Times, complaining that suffrage workers were essentially soliciting sex by having “pretty young girls” sell suffrage pencils on the street. There was the Wall Street Broker who hawked colorful suffrage pins on the sidewalk much like stocks to the delight of the crowds surrounding him.

There was the waitress who was ordered to distribute anti-suffrage matches but hid them under a group of pro-suffrage posters instead. There was the suffrage worker who was moved through French customs quickly when the guard saw her suffrage button and sympathized with her. There were attempts on the part of police to ban the sale of buttons at demonstrations. And in England, agents for the authorities disguised themselves as sympathizers by wearing pro-suffrage badges only to harass and beat suffrage workers.

Writing this book, then, has been a cathartic experience, and my collection continues to grow in meaning. My editors have been enthusiastic about the project and have even allowed me a color insert even though they ordinarily do not publish in color. Suffrage artifacts are too graphic simply to be reproduced in black and white. Finally, I would love to correspond with anyone who is interested in suffrage memorabilia, either from the standpoint of a collector or from someone who is interested in these pieces as a reflection of history.

“Women’s Suffrage Memorabilia: An Illustrated Historical Study,” will be published in April/May 2013. It consists of a discussion of over 70 different types of memorabilia that were produced by activists to promote the cause, including postcards, buttons, ribbons, sashes, sheet music, china, and toys and games. The book relies on numerous period references to discuss how important memorabilia was to the movement, and includes a number of fascinating stories about individual objects. With over 215 photographs, many of which are in color, this work is intended for both collectors and historians. Link to author’s website.