by Kenneth Florey

Women, Cars, and the Suffrage Movement: Part I

Early on in the history of the modern suffrage movement, there was a strong connection between the development of the automobile and its adaptation by suffragist activists. In part, cars were functional and could be used by various movement organizations to ferry workers from campaign office to campaign office and from rally to rally. In 1911, for instance, the wealthy American socialite, Mary Dodge, gave Emmeline Pankhurst of the English Women’s Social and Political Union a new Wolseley that allowed her to travel to suffrage events with not only her luggage but also with WSPU literature and other materials that proved helpful when she delivered her speeches.

This functional purpose was also a reflection of the emergence of women in public life, an emergence that was recognized not only by the suffragists themselves but also by manufacturers who saw the possibilities of a profitable new market. The Peerless “38-Six” car was promoted in magazine advertisements as early as 1912 as “most satisfying for women to drive” because of its electric starting and easy steering.

In 1915, American suffragists presented NAWSA’S President, Anna Howard Shaw, with a Saxon automobile, painted in the suffrage color of yellow. The company went on to maintain loose ties with the movement, directing some of its advertising not only to suffrage workers in particular but also to women in general.

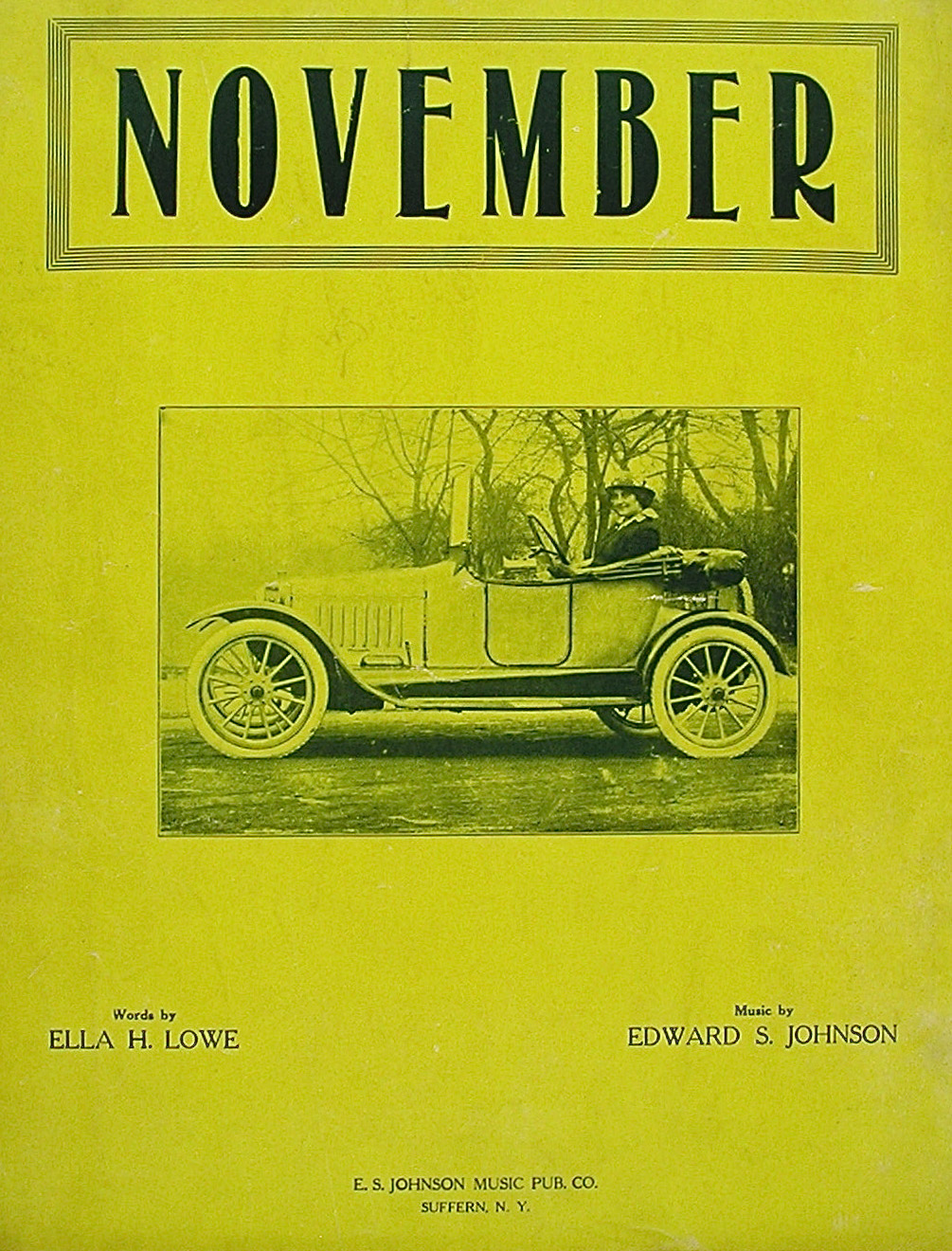

So closely was the Saxon to become identified with the movement that a song published in 1915 by Ella Lowe and Edward Johnson called “November” heralded the use of the car for suffrage activities: “In a Saxon built for two I will save a place for you in asking for the franchise next November.”

Automobiles driven by women were to become a standard feature in suffrage parades, serving not only as floats but perhaps also as a not-so-subtle message pertaining to the liberation of womanhood. After all, it was not that long ago that even women on bicycles were subject to intense derision and mockery.

President Grover Cleveland forbade the wives of his cabinet members from riding bicycles, and Belva Lockwood, candidate for President in 1884 and 1888, was lampooned in the press for her use of a tricycle that she used to save time when she conducted her business rounds. In England, Emmeline Pankhurst’s driver, Aileen Preston, was the first woman to qualify for the Automobile Association Certificate in Driving, so new even there was the concept of the freedom of women to command their own automobiles and thus their own movement.

COMING SOON: Video about suffrage automobiles.

Articles by author Kenneth Florey during May 2013 about automobiles and wagons used in the suffrage movement. Ken’s web page and order form for his book, below. Images from the suffrage memorabilia collection of Kenneth Florey.

One Responses

I think the symbol alone of seeing women driving and using the autos would have been a great message to the wider public back then, and of course we know they were very creative and used whatever they could to further their message if independence and freedom, so it’s no surprise they used the autos for a ‘functional’ purpose. Thumbs up to them for ingenuity!